This quote, falsely attributed to Abraham Lincoln, is inspirational but scary to anyone new to ax-manship. I get the idea of the quote. But four hours to sharpen an ax?

Okay, if an ax is in really bad shape, you could spend a few hours on the workbench. But once you’ve spent time achieving a keen edge, you’ll understand why Horace Kephart advises to never loan your ax to someone unless they know how to use it. A dull abused ax a misery to swing and quite a job to bring back to working-sharp.

Scary Sharp Axes

I’ve always kept my working axes Sherpa Sharp, which by definition is a bit honed enough for a day of feeling, limbing, and bucking logs without needing to be touched up in the field. My method changed four years ago when Craig Roost (aka – Rooster) introduced fellow Axe Junkies to his simple Scary Sharp method.

If you’ve never been able to shave arm hair or slice newsprint with your ax, give Rooster’s Scary Sharp method a try.

Below is a list of stuff I use to sharpen my axes in the shop and field.

My Shop Tools

- Wet/Dry Sandpaper: Progress from 220, 400, 600, 1,000, and at times 1500 – auto parts stores carry this sandpaper in 9″ x 11″ sheets

- Bench Belt Sander: 80 to 120 grit

- Drywall Hand Sanders: One for each wet/dry sandpaper grit to speed up the process

- Leather Strop: A barber’s strop glued to a board

- Green Buffing Compound: Rub into the leather strap

- Buffing Wheel: Rarely use this machine on working axes

- Files: Bastard file is used for bits needing to be re-profiled or when nicked/chipped

- Rigid SuperClamp: This floor vise has revolutionized my shop

- Safety Equipment: Leather gloves and eye protection

- Ax Puck: Medium and coarse duel sided grit

- Strop: Leather belt, leather ax sheath, or wood

- File: A small bastard file

- DIY Fixin’ Wax

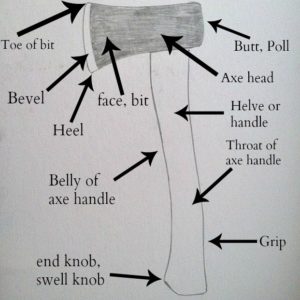

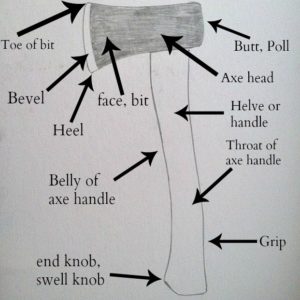

Refer to the Ax Anatomy chart below if you’re unfamiliar with any of the terminologies.

Related: Avoid These Prepper Mistakes

Shop Maintenance System

You may sharpen your axes differently. This is the system I used to maintain my working axes. The condition of vintage axes I restore varies from light rust removal with a wire wheel to major vinegar bath and material removal with a file. This post is not intended to cover the complete restoration process of old axes. It’s a maintenance step to keep working axes sharp. Even “out of the box” axes likely need to be honed before severing wood fibers.

Belt Sanding

All new-to-me vintage ax bits typically go on the belt sander first. Hold the ax head so that the sanding belt moves from the poll of the ax to the bit. The other way around will end up severing the sanding belt. Work the bit from toe to heel on the part of the belt that gives way to pressure. In this way, the belt conforms to the convex grind angle of the ax bit.

This is my sweet spot on my homemade belt sander.

Make a few passes on one side and repeat on the other side of the bit. I sand both sides maybe three times with 80 grit depending on the need. Swap out to 120 grit and repeat the process.

I don’t use leather gloves. I want to feel the warmth of the ax bit during the sanding process. The ax head is dipped in water several times throughout the process to keep it cool and preserve the temper of the bit.

Hand Sanding

Hand sanding can be done without a vise. However, my Rigid floor vise makes the process easier and faster. Clamp the handle in the vise with the axhead perpendicular to the floor. Stand to the side and behind the bit, you’re going to sharpen. Now would be the time you’ll want to wear leather gloves.

Cut a strip of each grit to fit the drywall sanding handle(s). With as much sharpening as I do, multiply handles with each grit attached saves time from having to change out sandpaper if using only one handle. Plus, I had these handles in my drywall box from my handyman days. Using them to sharpen axes is way more pleasurable than their intended use.

Related: The Best Places To Live Off The Grid

Begin swiping from heel to toe of the ax bit with the 220 grit sandpaper. Move the sander in a semicircular motion. You’ll be reminded of Dustin Hoffman’s character in the movie Rain Man with all the counting you’ll be doing. I stroke one side 30 times. There’s no magic number to this and you don’t have to count – it’s just what I do. I flip single bit axes in the vise and sand the other side 30 times. For my double bit axes, I reposition on the opposite side and stroke the second bit before flipping the ax.

On the second grit, 400, I change from a “heel to toe” direction to a “toe to heel” stroke. This helps me see how well I’m replacing the previous scratches on the bit left by the 220 grit. Continue changing grits and direction until you make it to the highest sanding grit. Most times, I only need to go to 600 grit and a good stropping to get my working axes Sherpa Sharp. I rarely go up to 1,500 grit unless I’m sharpening a new-to-me ax.

Stropping

I glued an old leather barber’s strop to a wooden handle years ago. I rub green compound into the leather and use it in the same way as the sanding handles. I only strop the bit about 10 times on each side to remove any burrs and give the bit a mirror finish.

Rooster even made a strop for a drywall sanding handle.

Rooster’s method produces remarkable results. The foam pad under the drywall sanding handles allows the sandpaper to conform to the convex shape of the bit. So simple a novice can do it!

Field Maintenance System

There have been times when I lay into a tree and notice the bit not penetrating the wood fibers very well. This is usually because I failed to sharpen my ax in the shop before heading out. You may be tempted to overcompensate with more power in each stroke. Not a wise idea. This will lead to early fatigue; damage to the handle, and possible injury. Stop swinging and touch up the bit.

Puck It

For years I’ve used a Lansky Puck to touch up axes in the field. The course side is 120 grit with the other side being 280 medium grit. The medium grit (280) is all I used to hone in the field. I use water, not oil, on my puck since I always have water available. Sometimes I use it dry. Either way, I rarely use this stone if I’ve “Rooster’d” my axes in the shop beforehand.

Grip the puck so that your fingers and thumb are not hanging over the bottom of the stone for obvious reasons. Make several circular strokes down and back on one side of the ax bit. Flip to the opposite side of the bit and repeat. I like to hold the ax so its bit in my line of sight. I can adjust the angle of the puck to meet the bit edge as needed. For double bit axes, I sink one bit into a stump to hold the ax in place while sharpening.

I strop the edge with the leather ax sheath to remove burrs as a final step. A piece of wood can also be used as a strop.

I apply a coat of DIY Fixin’ Wax to the axhead when I think about it. This helps to prevent rust, which isn’t usually a problem until carbon steel sets for a while. Due to the beef tallow content in my Fixin’ Wax, it also helps to remove pine sap from my tools.

Steven Edholm (SkillCult) has a video of how he made a field “puck” from a Japanese water stone. Pretty creative. The stone has 250 and 1,000 grit sides. I have a stone like this but haven’t made the field puck yet.