Editor’s note: This article was written by Maybell Nieves, a professional physician from Venezuela.

Dealing with this subject has been quite difficult for me. Both the concept of the state stripping you of everything and the SHTF concept have as many backgrounds as diverse interpretations, so trying to approach this from a single point of view is a complicated task.

In my country, Venezuela, after 20 years of “revolution,” we have bottomed out and learned to live in situations we never imagined (so much so that I was able to write an article on survival techniques I never imagined myself using on daily basis).

It’s not that the governments before Hugo Chavez were much better. But there was a much more stable political and economic situation with access to the international market.

That’s probably why those first few years didn’t really feel like something was taken away from us. In addition, the newly elected president had a 60% popular approval rating and promised endless opportunities for the neediest people.

One of the first economic policies was the implementation of exchange control, currently in effect. Any operation with foreign currency was managed by the state. Later came the control of the prices of basic products, which caused the disappearance of those items and initiated a black market that is also very much in force to this day.

The decay was soon seen in many aspects. There was no longer maintenance on public roads, and public services failed often until reaching the point of constant failures of electric service, even for days.

The public health situation is also getting worse and worse. As a health professional, I have seen this deterioration for the last 10 years.

I am an oncologic breast surgeon. In Venezuela, breast cancer is the main cause of death from cancer in women. However, in the hospital where I work, the most important hospital in Caracas, there are no basic services for this issue. No chemotherapy, the radiotherapy equipment has been inoperative since 2015, and surgical procedures are suspended every week.

For me, as a doctor, it is frustrating not to be able to help my patients in any way. Just last week two breast cancer patients who were going to the operating room were suspended for the fourth time in a row. This time the anesthesia machine was failing.

The purchasing power of the Venezuelan citizen also decreased. It seemed to have happened from one day to the next, but if you look at the political situation since 1988, the decline took a long time; all that was left was to hit rock bottom.

Finding ourselves in extreme situations makes our defense system act in a primitive way. This means activating the fight or flight response at any time within any context—and yes, the state takes advantage of that.

The state will rip you off, but it doesn’t happen all of a sudden. There are a lot of logistics; it takes a long time to develop the kind of policy that makes citizens totally dependent on the state.

You start by losing something unimportant, like some kind of monetary bonus now given to you as government-run grocery store credits, and you end up losing your freedom and all kinds of rights, including freedom of speech and protest, but these issues are so extensive that they require an article of their own to explain them properly.

The state has taken charge, with great success I must say, and you are now living in fear of the so-called public authorities, meaning police and military police, since they serve as pro-government forces of repression.

Many of us have lost the incentive to go out and protest. We did it for more than 10 years. However, I have seen the evolution of the manifestations before and now.

I remember 2003 when repression was minimal, almost non-existent. Today many friends who still have the strength to continue have gotten gas masks in order to defend themselves from the hundreds of tear gas grenades used by the authorities that should be defending people.

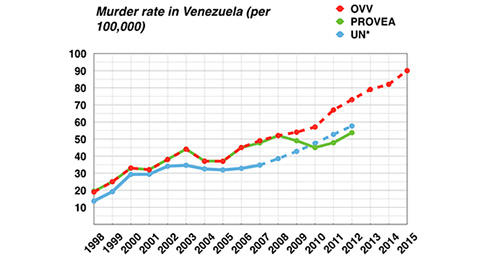

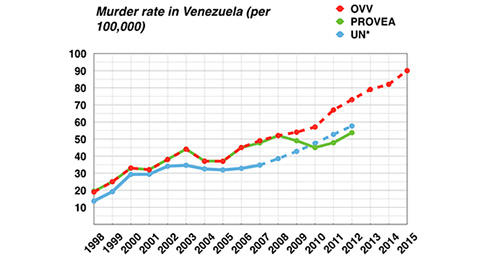

In any public protest, savage repression is a constant. That violence is what we Venezuelans have become used to.

Defending oneself from these kinds of problems is as difficult as trying to explain them. Many have chosen to leave and seek a future in other countries. That way the state even strips you of your own country by causing you to become self-exiled.

I don’t blame them. We all have more than one family member or close friend who has been kidnapped or stolen from violently, and sadly, all we can say is “You should be thankful you weren’t killed”.

Personal security becomes a problem of epic proportions, to the extent that going out on the street is considered a risky activity—a risk to which, unfortunately, you have to get used to in order to live a normal life.

Living in a place where a good monthly salary fora top executive, for example, does not reach $100 a month, is not easy, especially taking into consideration that a basic shopping list for a family of four can cost up to $140 monthly.

So the mismanagement of incompetent and corrupt civil servants results in the deep separation of three social classes: extreme poverty, which represents more than 80% of the population and is totally dependent on the government; the working middle class, which manages to subsist through one or two basic incomes plus the economic help of family members abroad; and those who do business with the government and can live in a very comfortable, ideal world that has nothing to do with reality.

Of course, there are exceptions to this, and some people have high incomes without being involved in dubious businesses.

It is sad to see how fourth-level professionals, trained in the country, must leave in order to provide for their families.

I know it is not a unique situation in the world—it has happened and will continue to happen—but it is very different to read about it than to see it sitting in the front row or even being the leading character.

Nowadays it is the common denominator, and more and more qualified professionals and technicians step into the international airport in search of a better quality of life.

I think the worst part of all this is the desolation sown in all of us. It seems to be an endless story, with the political disqualification of opposition leaders, political prisoners, and many more vexations.

Writing all this is not easy, but it makes me reflect. It is an exercise in introspection. Without a doubt, the state strips you of everything in its eagerness to stay in charge. That’s the way they do it.

There comes a point at which the only thing in your mind is to know if you will return home alive. Everything else is secondary. At that point, the state has already massacred you internally. You can never be the same again. I’m sure I am not.

Even if you are a person who is not involved in politics, an “apolitical” citizen, in this state of anarchy, you have to fix your position.

As Desmond Tutu said, “If you are neutral in situations of injustice, you have chosen the side of the oppressor.”